A few days ago I stumbled on a strange tweet that was highlighting a controversy about scalar type hints.

Scalar type hints & return types vs no scalar type hints & return types is #PHP's new spaces vs tabs

— Cees-Jan 🔊 Kiewiet (@WyriHaximus) 19 maggio 2017

After asking references about this, someone alluded to this very short video: “PHP Bits: Visual Debt” (it’s only 3 minutes, please watch it before continue reading). After that, the author of the video was dragged into the conversation, and it blew up into a big tweetstorm in the following few hours.

The core of the controversy was the fact that the author of the video classified as visual debt a lot of stuff in his PHP example, like interfaces, scalar type hints and the final keyword.

My opinion on the matter

I can agree with the bottom line of the video:

Am I necessarily getting a benefit […] ? Question everything

Every choice in our line of work is always a trade-off between benefits and cons, and every new introduction in a projects should be evaluated and agreed upon between team members. But my personal preference leans a lot towards the opposite side in this specific matter: as I stated in a previous blog post here, I love the new additions that PHP 7 brought to us like scalar and return type hints, and I use them as often as I can, because I discovered that they bring a lot of benefits to the code that I write.

Probably this was influenced by the fact that previously I worked with C++, where types are a lot more intrusive compared with PHP 5; but over time and with usage, I learned the great benefits that we can achieve with this addition to our PHP 7 codebases. In general, I think that type hints, and other language features that create a more “rigid” code, are helpful during the evolution of a codebase, and so they are really needed in long-running projects, where the maintainability of code is crucial. It may be less true in a “release and forget” type of project, but I think that it would still be like betting againt oneself.

In this blog post I would like to explain myself and the reasons behind my arguments, recounting them.

Scalar type hints as safeguards

In the video, the example had all along this class:

class Event implements EventInterface

{

protected $events = [];

public function listen(string $name, callable $handler): void

{

$this->events[$name][] = $handler;

}

public function fire(string $name): bool

{

if (! array_key_exists($name, $this->events)) {

return false;

}

foreach($this->events[$name] as $event) {

$event();

}

return true;

}

}

The author suggests to remove all type hints, since the code should still work and you could get rid of a lot of additional, not needed complications. I disagree completely with this.

Type hints are safeguards here, because they let you reduce to the bare minimum all the checks that you should do here before accepting the input arguments:

- because it’s used as a key for an array,

$namecan only be a string (or an int, but it would not make sense) - the

eventsproperty can only accept callables, because its elements are invoked inside the foreach of thefire()method - because we don’t need to insert additional

ifs in our methods, we reduce the number of possible paths of execution, hence reducing the number of cases that we need to check in our tests.

Type hints and interfaces as contracts

In the video, it was suggested to also get rid of the interface:

interface EventInterface

{

public function listen(string $name, callable $handler): void;

public function fire(string $name): bool;

}

I agree that an interface should be written only if needed, like if you want to write multiple concrete implementation of it with different inheritance hierarchy. But this doesn’t mean that we will not have any interface at all: we still have the concrete implementation.

That is not the same of having a pure interface, but we will still be able to determine a contract, a list of method signatures that tells us what that object will accept as valid method calls. This kind of contracts are a must in object oriented programming, because they dictate how your object will interconnect, communicate and cooperate, and they are especially useful in combination with stricter type hints and unit testing.

When we write unit test, we use the real instance of the class which is under test, and everything else should be mocked. That means that we will use some test mocking library (i.e. I prefer Prophecy, which is included in PHPUnit) to mimick the behavior of nearby objects.

How type hints would help us in this case? If we would have to mock the EventInterface (or the concrete class, it’s unimportant here), having the return type hints for example would help us in writing good mocks, and not wrong ones.

But how? Nearly every mocking library creates a mock extending at runtime the original class, since the mock needs to pass every check and type hint as if it was the original class; this means that it can’t change the method signature, hence preserving the original return type hint.

This will translate in errors and test failures if we would write a mock that doesn’t return the proper type, like in this example:

class Person

{

public function shout(): bool

{

$event = new Event();

if ($event->fire('shout')) {

// someone was listening!

return true;

}

// ...

}

}

class PersonTest extends PHPUnit\Framework\TestCase

{

public function testShout()

{

$event = $this->prophesize(EventInterface::class);

$event->fire('shout')

->shouldBeCalled();

// ...

$person = new Person();

$person->shout();

}

}

$ phpunit

# ...

1) PersonTest::testShout

TypeError: Return value of Double\EventInterface\P2118::fire() must be a string, null returned

This mock, once used, will make the test fail. Why? Because the fire() method can only return a boolean, and by default (if not instructed differently) Prophecy’s mocks will return null. Without the : bool return type hint, the mock would return null but the test would not fail, and the class under test would silently cast or interpret the return value as false, possibly causing an unintended behavior or a false positive.

This means that having complete type hints in your interfaces and method signatures only makes your code more cohesive and your unit test more robust; this kind of enforcing helps a lot also with refactoring, since changing a method’s signature would cause failures in all the related tests that include a mock of that interface, as it could become inconsistent and unreliable after this change.

Use interfaces as behavior checks

One of the counter example that popped up during the discussion on Twitter was this one:

class Fireman

{

// ...

}

class Building

{

public function putOutFire(Fireman $fireman);

}

$building->putOutFire(new StrongAndAblePerson()); // type error!

This was cited to show how sometimes type hints can be a hindrance more that something helpful in your code: why a strong, capable person shouldn’t be able to put out a fire? Who’s the Building class to decide that? Are we maybe violating the Single Responsibility Principle?

I think that this is misguided for a simple reason: it was wrong to check against a concrete implementation instead of an interface; and that’s not evident because, in my opinion, the example was cut too short.

Let’s speculate on the content of the putOutFire() method:

class Building

{

public function putOutFire(Fireman $fireman)

{

$fireman->wearProtectiveGear();

$fireman->shootWaterAtFlames();

}

}

Why we have a type hint in the putOutFire() method? Surely because we want to rely on some method that a Fireman instance would give to us in the method body (i.e. the wearProtectiveGear() and shootWaterAtFlames()); if we remove the type hint, we would have no guarantees that those methods exists on the argument, and we would have to either use a method_exists() call twice (oh, the horror!) or expose our Building class to a possible fatal error.

To take the example further, we can make the StrongAndAblePerson capable of put out a fire if we extract the needed methods in an interface, defining a contract of what our putOutFire() needs to know and use:

interface TrainedFireFighter

{

public function wearProtectiveGear(): void;

public function shootWaterAtFlames(): void;

}

class StrongAndAblePerson implements TrainedFireFighter { ... }

class Fireman implements TrainedFireFighter { ... }

… now we can have the putOutFire() method with a broader type hint, that would accept both a Fireman and any other class that implements the TrainedFireFighter interface:

class Building

{

public function putOutFire(TrainedFireFighter $firefighter)

}

The final keyword

The only point of the video which I find relatable is the remark on the final keyword.

Apart from the funny joke (“I’m not your daddy!”), I find the final keyword not very usable in closed projects, since its only usefulness is to impede the extension of some object. When the persons that could work on a codebase are well known and they can be coordinated, I think it’s better to leave that liberty to the coders, and just have an agreement on what can and cannot be done with that class.

On the other hand, this keyword becomes useful when we are talking about open sourced code: using it is a clear statement that reduces the surface of the API that the library is exposing to end users, in the same way private is limiting access to properties.

Straightforwardly, the maintainer of the code is saying that this class is not extensible, because it may change internally without notice; this concept is also well explained by Marco Pivetta in his signature “Extremely defensive PHP” talk (which we cited also in our previous blog post, see related slide here) and in his blog post about it.

A practical example

I would like to conclude this blog post with a practical example. I maintain facile-it/paraunit, a parallelization tool that works on top of PHPUnit. In the past few days I was working on supporting PHPUnit v6, and that lead to bumping the minimum PHP supported version of the package to 7.0: https://github.com/facile-it/paraunit/pull/93.

Since previously the minimum supported version was PHP 5.3, I took the opportunity to go over the whole codebase and clean it up, using all the new language features that I could now take for granted: ::class shortcuts, array short syntax, but more importantly the aforementioned scalar and return type hints.

This is the perfect example to show that adding those type hints on already working code made a non-trivial difference even if I wasn’t changing the objects’ behavior, and it forced me to fix some of this stuff:

- it forced me to define more explicitly a default behavior, since a

nullwas no longer accepted in place of a string - this also lead me to write an additional test for an uncovered, very common case

- it made me realize that I had a regex silently failing returning a bad result, and I had to take better care of it, leading to a simpler and more robust approach

- this lead to additional tests too

- it made me discover a specific behavior of the SPL file iterator classes

Strict types enforcing

In the last part of this PR, I also added the declare(strict_types=1) directive everywhere in my code. This directive changes the behavior of type hints: with it, passed values are no longer silently casted (if possible) to the type-hinted, required type, but instead they trigger an immediate error if the type doesn’t match; for example, passing a "10" string into a int or float type hint will no longer trigger an automatic conversion to 10 or 10.0, but trigger an error.

I would admit that this is a matter of personal preference, and I would not suggest to use this everywhere, especially if there isn’t a very thorough test coverage; it may lead to unneeded failures in very unsuspecting places, and it may cause friction when intergrating code with external libraries that take advantage of the implicit type casting that PHP has always done.

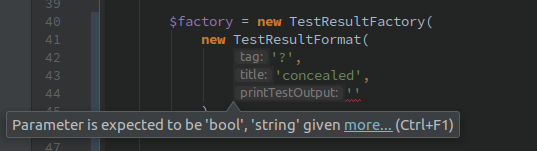

But even in this little use case, it lead to discover a small issue with an outdated test code, were I was passing an empty string instead of a boolean: that happened because I refactored a constructor some time ago, and I forgot to update the tests, and I missed it since the tests were not failing. The error was even well highlighted by my IDE now, but before it was casted silently to a bool, and it matched the expected behavior by sheer luck!

Conclusions

Type hints and other new PHP language construct help writing more cohesive, rigid code, that may lead to some “pain” while writing code and (mostly) tests; but this effort is just paying in advance: a lot of bugs get discovered earlier, and refactoring and changing code become easier, since pieces of code that doesn’t match anymore are more visible.

In the example PR, the amount of changed code that is not method signatures is trivial, but I drastically reduced the amount of possible deviations that my code could take if a wrong value is passed through it, and I fixed and tested a few additional cases that I was forgetting about. Also, the usage of the declare(strict_types=1) enforces even further this approach, raising the confidence that I have in the codebase.

Share this post

X

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email