What is this post about?

Developing a project or a product implies, for the engineering teams, the need to make many decisions to reach their goals. Therefore, the teams are often faced with an inevitable and usually not-so-exciting step: capturing and recording significant decisions. This post will give you a taste of what it takes to make decisions during project or product development and will provide you with a standard that can be used in different contexts.

What to capture and why?

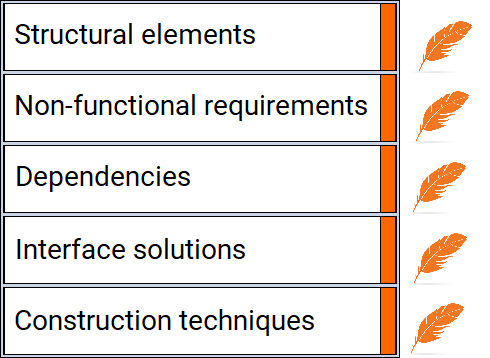

In the article Architectural Decisions - The Making Of, Olaf Zimmermann addresses the need to understand which decisions are significant enough to be recorded and defines significant decisions as "the ones that are hard and costly to change". These decisions are most likely to surface when talking about integrating dependencies, implementing interface solutions, adopting construction techniques, and introducing structural elements or non-functional requirements. Decisions made in these instances are rarely self-explanatory, nor deductible from the code. If we fail to record the reasoning behind them, we might encounter a Why? question later on from a new team member or our future selves.

Aware of the importance of capturing decisions, we might be wondering how to choose the right format. Before getting into what is available today in terms of templates and standards, let’s briefly dive into the history and try to understand what brought us here.

Architectural decisions: evolution distilled

In the early 90’, with the rise of software architecture studies, the term Architectural Decision started to gain importance. The rise was followed by a boom in the 2000s when the term established its presence once and for all in the sphere of Architectural Knowledge Management (AKM). Since then several formats for capturing Architectural Decisions were proposed and even included in the standards like arc42. The boom led to the production of several templates suited for capturing decisions. More often than not these templates were complex and required substantial effort to be compiled.

Today the situation is different. The need to be more responsive to market needs has made documenting software architecture decisions as important as recording any other meaningful decision. At the same time, the tools and formalism are lighter to favor their adoption and continuity of use.

MADR: an agile formalism

If you work in an agile environment, you know that often decisions are made along the way and have to follow the same fast pace as the project development. In this context, bite-sized pieces that document decisions are easier to produce and consume and therefore often preferred to more detailed ones.

Some of you might have even stumbled upon one of many articles and studies that aim at providing the best way to capture decisions. In that case, you have probably encountered the formats such as Y-statement and MADR. Both of these formats managed to establish their prevalence due to their slim and agile nature which perfectly reflects the fast pace of the current software engineering reality. In this article, we will focus on the MADR format.

These four letters reference one of the most widely adopted formats for capturing architectural and other important decisions, but do we know what they mean? Let’s break them down. Markdown is the syntax chosen for capturing these decisions. A stands for Any decision, but given its roots, it can often be limited to architectural decisions. A Decision is a choice that has an impact on the software project or product, while a Record is a document that captures a single decision, its context, and its rationale.

MADR: specifications and template

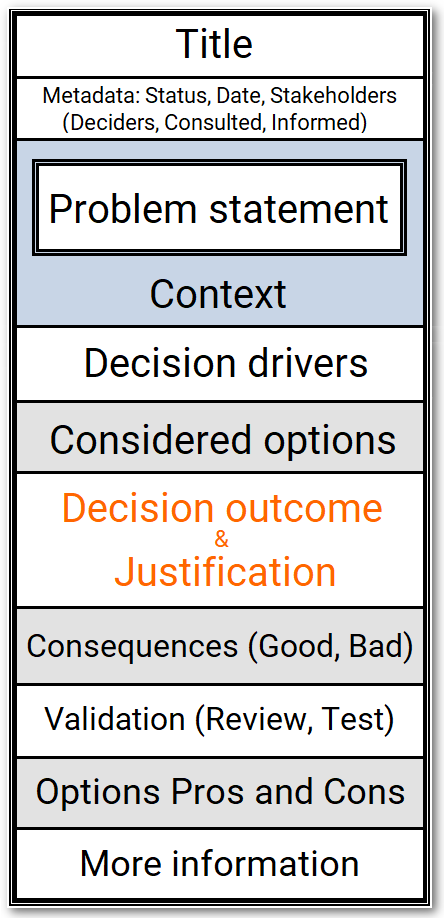

The consequence of the MADR format is version 3.0 of the MADR template, available in the MADR project on GitHub. The template consists of a limited number of sections, dedicated to capturing different aspects of a single decision. The first two sections are reserved for the ADR title and its metadata. The core of the template reflects a typical decision-making journey. The initial steps involve the identification of the problem and its context, and the analysis of the goals and desires driving the decision. Next is the evaluation of different options and their pros and cons. Once the final decision is made and enforced, it is time to record its consequences, such as improvements and added efforts or risks and to evaluate its implementation through reviews and tests. The last two sections contain additional information. Here we find the pros and cons of considered options and information that traces the realization and outcome of the final decision, its links to other decisions, and other relevant details.

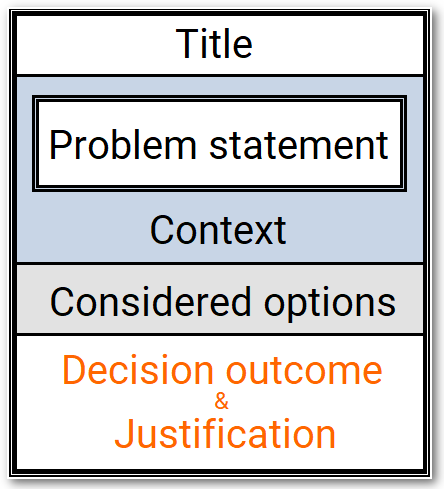

The reduced version of the template, MADR light, puts an even major emphasis on the lean and agile approach to capturing decisions due to its condensed nature, while still recording all relevant information regarding the decision. Let’s now take a look at this version of the template and its sections.

The Title of an ADR conveys the crux of the problem and the decision made to address it. The Problem statement is briefly described and placed within the Context. The other Considered options, later discarded, are listed. The final Decision outcome is clearly stated, complete with the Justification for its adoption. If we were to translate the template using another lean and widely adopted ADR standard, the Y-statement, the derived sentence would be: In the context of A, facing problem B, we neglected C and decided on D, because of F.

MADR: consistency enabled

The template simplifies the creation of decision records and ensures that all the relevant information is captured, but what makes the difference is the consistency of its implementation. It is not uncommon for engineering teams to be reluctant when it comes to capturing decisions. One of the main reasons is the fact that this task deviates from the usual workflow. Not only it requires them to switch from their usual activities to writing, but it calls for the use of different tools.

One of the ways to ensure the consistency of capturing decisions is to keep them as near as possible to the primary tool used by the engineering teams, their Integrated Development Environment (IDE). The Markdown syntax is suited for this purpose and allows for the ADRs to be placed alongside the version-controlled code project.

Conclusion

Adopting the light model of the MADR template is one of the possible answers to the questions raised on the boundaries between frenetic production and the need to trace and document the evolution of an engineering project or product. MADR light allows for reduced documentation efforts while still providing the added value of recording the reasons and consequences of the choices made. This formalism sees increasing adoption even in big tech companies and not without a reason. It is compact and supported both in IDE and in separate tools that allow for integration in daily team activities, such as Backstage and other software catalogs. Thus, MADR light seems to be on its way to becoming another piece in the puzzle called Docs as Code.

Want to learn more?

Here are some online resources to help you explore this topic in greater detail.

GitHub

Articles and talks

- Oliver Kopp’s talk “Markdown Architectural Decision Records: Capturing Decisions Where the Developer is Working” (slides accompanying the talk are available here)

- Boris Donev’s article “Architecture Decision Records (ADR) With Azure DevOps”

- Michael Keeling’s piece “The Psychology of Architecture Decision Records”

The perspective of big tech companies

- MicrosoftGitHub - Code With Engineering Playbook “Design Decision Log”

- AWS Prescriptive Guidance “Using architectural decision records to streamline technical decision-making for a software development project”

Share this post

X

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email